Nursing at Hobart’s public hospital has come a long way since the colony was first established in 1804.

12th May is International Nurses Day, where we celebrate the value of nurses in our communities on the birthday of British nurse, Florence Nightingale (1820 – 1910) the founder of modern nursing.

Image: Wikipedia Commons

Prior to the innovations of Florence Nightingale, nursing was poorly paid and akin to domestic service. The earliest use of the English word nurse can be traced back to the 13th century, having derived from the Latin word meaning to nourish, reflecting the work of a wet nurse who was hired to breast feed the baby of another woman. This work later extended to the general care of children, as in a dry nurse – a woman who nurtures the children of others. By the 1600s this term extended to those who cared for sick people.

At the time of British settlement in Van Diemen’s Land, there was no training for nurses. The work of nurses at the Hobart General Hospital was undertaken by convicts who had to feed patients and clean up after them. Accommodation for nurses was within the sick ward which meant they were on call all day and night.

In 1824, the new Principal Surgeon for the Hobart General Hospital, Dr James Scott (1790 – 1837) sent a memo to the new Governor, George Arthur, that along with extensions and other improvements to the hospital, accommodation should be included for a man and wife team of Overseer and Matron to supervise the feeding and washing of the patients, as well as to ensure decorum among the patients. Respectability of the Matron was essential, but her nursing skills were never investigated. Dr Scott was firmly convinced that a good hospital was one where the male and female patients were strictly segregated and that they were controlled, calm and polite.

The Overseer and Matron were also given charge of the nurses – assigned convicts – to ensure that the patients received their full allocation of food and to check that the medicines and meals weren’t consumed by the nurses or sold outside the hospital.

For the next 30 years, the nursing staff consisted of male and female assigned convicts. By the mid-1850s, with the end of convict transportation and the expiration of convict sentences, the Hobart General Hospital had to pay for nursing staff, who were being increasingly hired from the free migrant population.

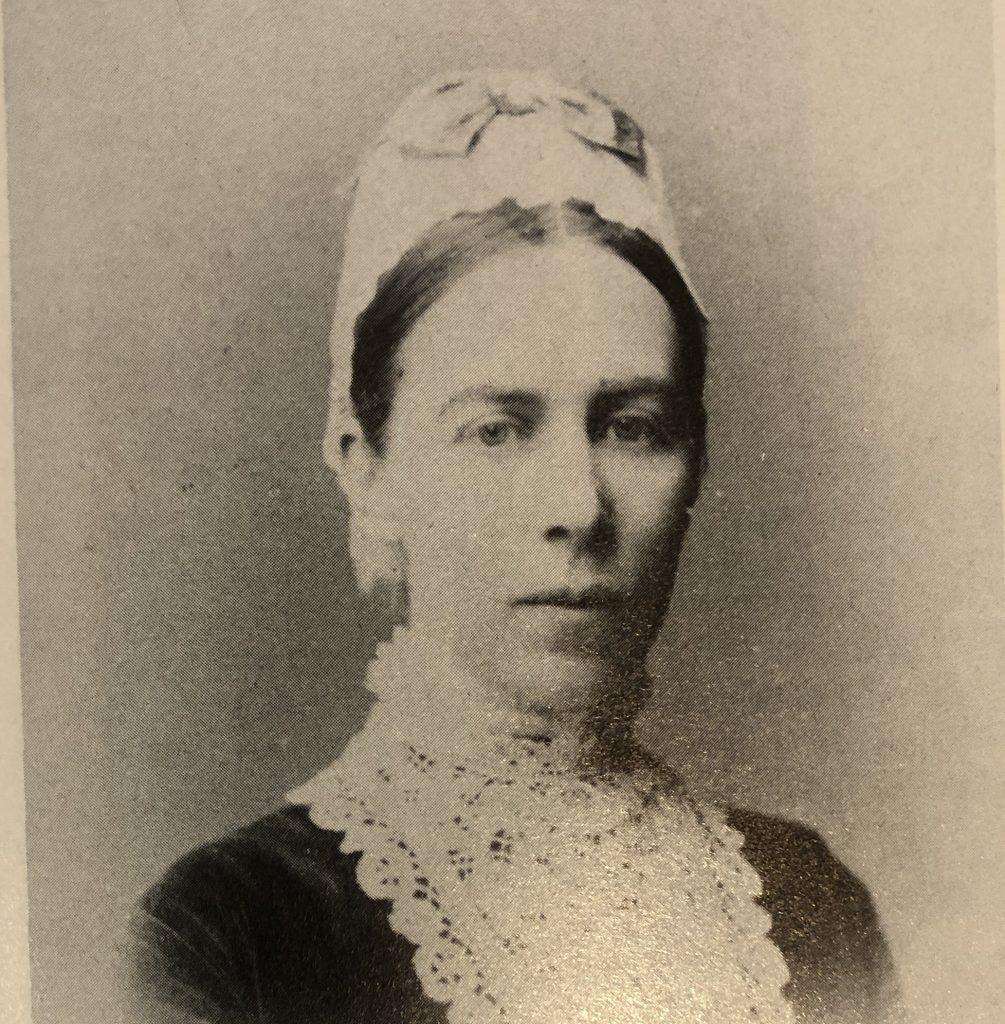

In 1874 an inquiry into the conditions at the hospital revealed that the Hobart Hospital wards were dark, dingy and of a quality greatly behind that of hospitals in England, Europe and Canada. Greater attention had to be paid to cleanliness of both the patients and the staff, as well as complete separation between infectious patients and all others. Most importantly was the urgent introduction of trained female nurses under the supervision of a new Lady Superintendent. The first Matron at the Hobart General Hospital was Florence Abbott (1849 – 1937).

Born in Hobart to a well known and distinguished family, Florence was the grand-daughter of the first Deputy Judge Advocate of Van Diemen’s Land, Edward Thomas Abbott (1766 – 1832). In about 1869, she travelled to Sydney to undertake her training as a nurse at the Sydney Infirmary where she trained under Lucy Osburn (1836 – 1891), Florence Nightingale’s envoy to Australia.

In March 1875, Florence Abbott returned to Hobart to discuss the terms of her role as the first Matron of Hobart General Hospital. She accepted the position, based on certain conditions. She insisted that she would have sole control over all nursing staff, that all the nurses would come from those she selected in Sydney. These would include four head nurses and 11 trainees, plus one male nurse and three servants. All of them were to be aged between 20 and 40 years. The Tasmanian government was to provide her with her own self-contained suite of rooms, as well as uniforms and accommodation for the nurses, plus a kitchen, mess hall, bathroom and toilets for the exclusive use of the nursing staff.

It took nearly a year – and three epidemics (measles, typhoid and scarlet fever) – before the government would agree to all of her terms. Big promises were made to Matron Abbott, and after she and her nurses started working at the hospital, many of the promised conditions were nibbled away. It took another 6 months, and the mass resignation of all the nursing staff, before all the conditions were fulfilled, and only then after a Royal Commission completed investigations into the hospital in 1877.

Finally, thanks in a large part to the efforts and persistence of Matron Florence Abbott and her nurses, the Hobart Town General Hospital Act, 1878, established a board of management for the hospital. The 17-member board included the Mayor of Hobart and four honorary medical officers of the hospital – but no nurses.

Matron Abbott brought about a complete revolution in the treatment of patients, as well as in the cleanliness and organisation of the Hobart General Hospital. She began training local nurses in 1878 as well as nurses for other hospitals around Tasmania. She brought in the rule that for every 20 patients in a hospital there would be a head nurse, with a graduate nurse and a trainee. Their medical instruction was supplemented by weekly lectures from the resident surgeon.

The value of the high-quality care of patients by trained nurses under Matron Abbott became clear with subsequent typhoid epidemics. The typhoid patients were cared for in the hospital by a group of dedicated nurses who put themselves at risk of infection. The nurses were greatly admired for their commitment and selflessness, and they acquired a very high reputation. Calls for public recognition of their work brought better conditions and improved training – as well as the creation of special medals to reward the courage and devotion of the nurses at the Hobart General Hospital. Gold medals were presented to 19 nurses in 1887 in recognition of their dedication.

As for Matron Abbott, she resigned in 1881 over a staffing dispute. Abbott ordered a nurse to scrub floor and when the nurse refused, she was instantly dismissed. When the hospital Board of Management supported the nurse against the Matron, Abbott resigned and returned to England. She spent some years as Matron at the Brompton Chest Hospital, and ended her career in 1891 when she married Dr Henry Taylor, the resident medical officer. Matron Abbott died in Sussex, England in 1937 and is buried at St Andrew’s Church, Steyning.

Image: gravestonephotos.com