When we think about conditions experienced by convicts and settlers in the first years of colonial Hobart, it is very easy to fall into the trap of the usual line: everyone had a rotten time, all convicts were illiterate, exploited, badly treated and they died young and miserable.

Deeper investigation of the early history of Hobart shows that things were not as bad as common mythology would have you believe.

With this in mind, and considering the 200th anniversary of the opening of the Hobart General Hospital, it’s a good time to look further into the state of the medical care in the early days of British settlement in Hobart.

I fully expected to find a different story to the usual assumptions of a scene of grime, suffering and deprivation. Surely things weren’t as bad as all that? Of course, compared to the conditions we enjoy today, the medical care for Hobartians in the first 20 years of the settlement would have been basic, but I expected things to have been on par with the other colonies. A little surge of local pride prompted my hope that medical care here in colonial Hobart was considered better than most Australian settlements.

I have been horribly disappointed.

How bad was it?

Medical care in colonial Hobart was terrible in 1804 and things didn’t really improve for the next 20 years.

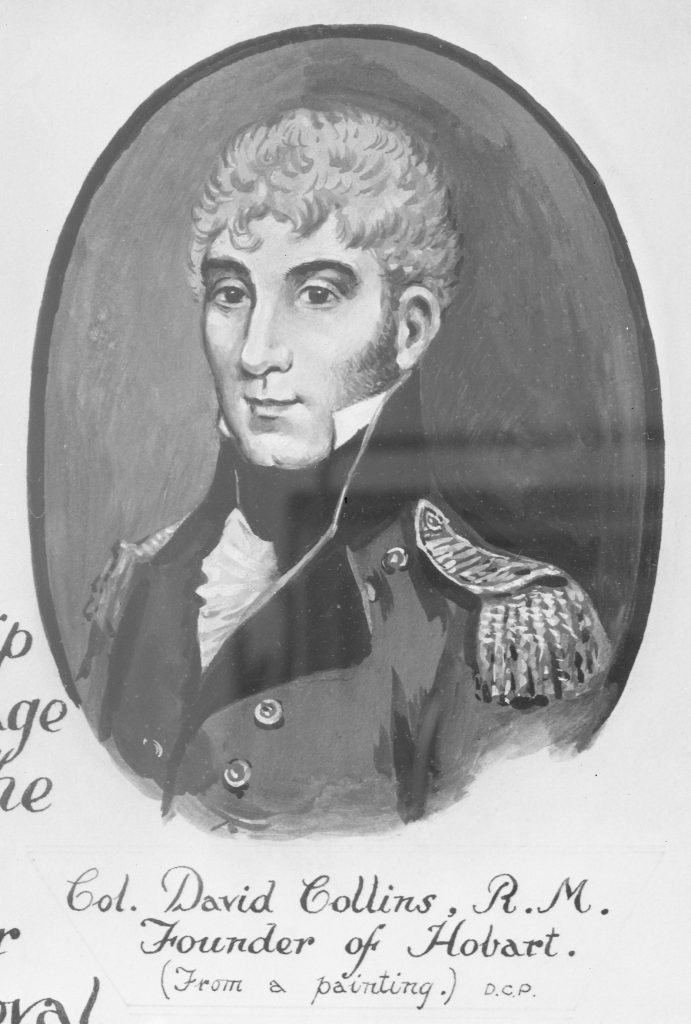

In February 1804, Hobart was settled by Governor David Collins (1756 – 1810). He brought with him 441 people, including 3 medical officers and a hospital assistant. On arrival many of them were on the sick list, suffering from scurvy and diarrhoea. They had departed England in April 1803 in order to establish a settlement at Port Philip on the south coast of Victoria, arriving there in October. Collins was disappointed with the area. The sandy soil wasn’t suitable for farming, much of it was swamp and there was little fresh water. After three months of struggle and illness due to tainted water and a shortage of fresh food, Collins removed everyone to Risdon Cove on the Derwent River in Van Diemen’s Land, to see what Lieutenant John Bowen (1780 – 1827) had been up to since he started his tiny British settlement there in 1803.

Here too, Collins found the soil to be poor and the water scarce, so he rejected the Risdon Cove site and moved his Port Phillip evacuees across the river to Sullivan’s Cove and so established the settlement of Hobart.

From the start conditions were difficult. Collins had to deal with a month of rain which caused coughs and colds, sending many to their sick beds. At least there was a good supply of fresh water from the Hobart Rivulet along which they pitched their tents – and into which they tipped their sewerage. The resulting poor sanitation meant nearly everyone came down with diarrhoea. The hospital tent was inadequate to the demands and the medical officers had little in the way of effective medicine and equipment to help the sick.

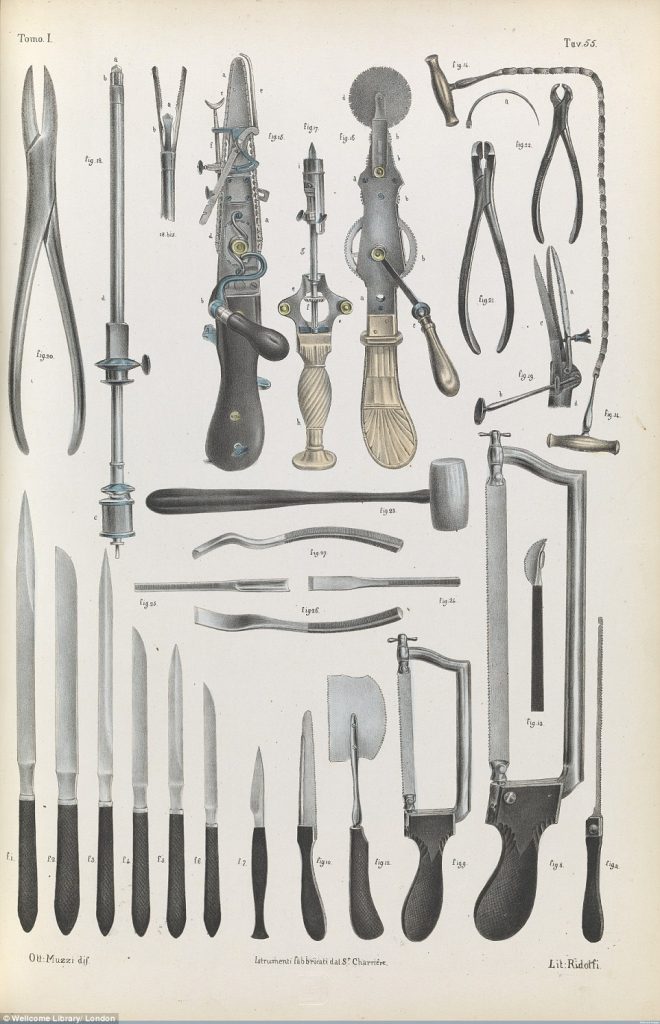

Each of the medical officers had been supplied with a chest containing medical instruments. When unpacked the medical instruments were old, second hand and mostly superseded. Collins wrote letters of complaint to London and the suppliers of the medical equipment, when asked for an explanation, were dismissive of his complaints that he had been given old, rusty implements. One supplier stated that the equipment was modern enough for the purposes of a convict colony, the same as would be fit for any hospital in the Royal Navy. A concession was made that yes, perhaps some of the shipment may have been a bit rusty, but that couldn’t be helped: the medical equipment had sat in London’s waterfront storehouses for a long time because no one else wanted it.

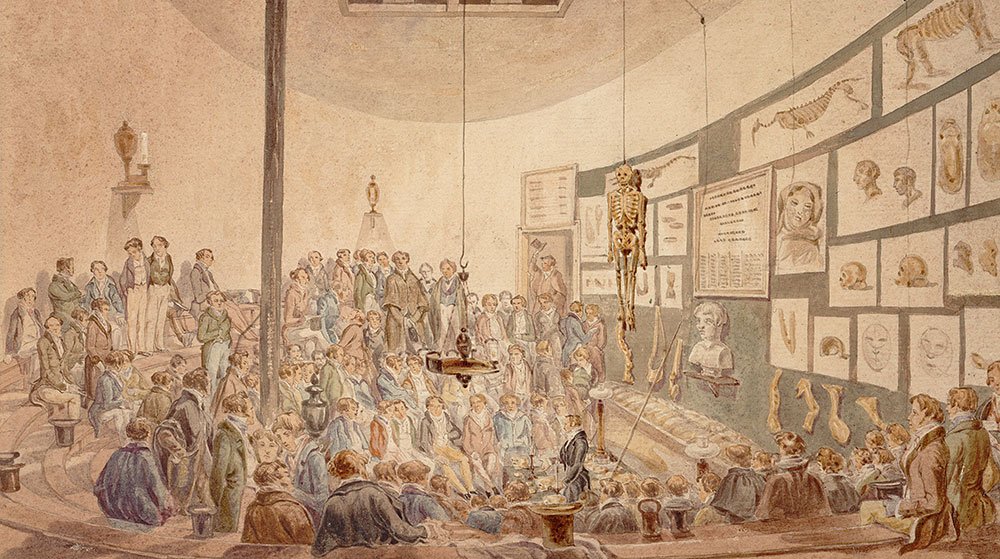

In the late 1700s, men who trained as surgeons served as an apprentice to a master for five to seven years, and if they could afford it, they would attend lectures and demonstrations.

This was followed by admission to a Guild, which granted a licence to practice. The now qualified surgeon could practice in small towns, join the Army or Navy or apply for a civil Government position in the colonies.

The day to day work of the surgeon at this time did not involve high risk operations. The majority of their work was minor and non-invasive, such as lancing boils, dressing minor wounds, pulling teeth, trussing ruptures and treating skin conditions like ulcers. The surgeons understood their limits and avoided dramatic procedures like amputations. They knew the risks of shock, blood loss and infection and so avoided cutting into the patient whenever possible. Fatality rates at the hands of surgeons were low. The majority of sick people would be cared for by family members in their own homes and the ailments treated by surgeons were done using low-level intervention, medicines and management.

The skills and qualifications of the medical officers sent with Collins were often called into question. The three medical officers, William I’Anson (1761 – 1811), Matthew Bowden (1779 – 1814) and William Hopley (1780 – 1815), had been appointed based on family connections and letters of recommendation from friends with influence – not on their outstanding medical skill and expertise. Their hospital assistant, former convict Samuel Lightfoot (1762 – 1818), had been appointed on the recommendation of David Collins, who had known Lightfoot since 1788 in Sydney. Collins had served the first fleet as Colonial Secretary, Judge Advocate and Lieutenant Governor. Lightfoot, sentenced to seven years transportation for stealing clothes, gained his freedom in 1793 and returned to England. In 1803 he applied to join Collins as a free settler in the establishment of the Port Phillip settlement, and was given the job of hospital assistant.

In Hobart, by December 1804, the three medical officers, with now 6 convict assistants, had treated 467 cases of sickness. They were struggling without sufficient food, medicine or effective medical instruments. Everyone was living in tents and rough huts, suffering the effects of long-term hunger and exposure through a wet and cold Autumn, Winter and Spring. By June 1805, one in ten of all new arrivals had died, most of them young men.

The colony relied on regular food and medical shipments from Sydney, and when supplies failed to arrive Collins was compelled to reduce food rations. With a population of less than 500 people, most of whom were afflicted with constant sickness and injury, there were limited numbers of people who were fit enough to undertake the work of finding local fresh food from hunting, fishing and farming.

In 1807 Governor Collins suspended Second Assistant Surgeon Hopley from his position for misconduct. After a severe reprimand, Hopely was returned to duties then he applied for and was granted 18 months sick leave. Hopley tried many times to get passage back to England on the ships that came in to Hobart, but he was unsuccessful, because he also wanted to take his entire, very numerous, family back to England with him. All the work at the hospital was now being undertaken by I’Anson and Bowden. Their convict helpers required full time supervision to prevent absconding, pilfering and malingering.

The colony struggled on and under the strain of it all, Governor Collins died suddenly in 1810. Principal Surgeon I’Anson was a pall bearer at the very large and extravagant public funeral. By this time the population had nearly doubled to just under 1,000 thanks to the flood of evacuees from Norfolk Island.

The military received medical care in their barracks by their own regimental medical officers and the colonial medical department treated everyone else, including all the sick and injured convicts. Permission was granted to charge others a fee for medical treatment, but in Hobart all the civilian sick continued to be treated without charge. The treatments were administered either as an out-patient in a day clinic or for serious injury or fever, by admission into the hospital. This was originally a tent until a small hospital hut was built near the waterfront after which rooms were rented in private homes.

As Hobart was a sub-colony of NSW (until 1824) permission to construct a public hospital had to come from the Governor in Chief in Sydney.

In 1811, this was Lachlan Macquarie (1762 – 1824) and shortly after taking up his new job, he arrived in Hobart in November on a tour of inspection. He visited all the government facilities and declared the conditions of the Hobart General Hospital to be the worst public facility of all. Food, medicines and bedding in the rented rooms used for the hospital were found to be insufficient and defective. Smallpox vaccines sent from England, which took a year to arrive, were inactive.

Principal Surgeon I’Anson had died shortly before Macquarie’s arrival in Hobart and Bowden was promoted to that position. Hopley, now fully recovered had remained in Hobart. He was ready to return to work and was appointed as first assistant surgeon.

Image: TAHO

Macquarie decided the hospital needed a permanent structure of its own and marked out where it was to be built, fronting onto Liverpool Street – but didn’t provide the funding to commence construction, much to the frustration of the new VDL Governor Davey (1758 – 1823) who arrived in 1813.

Principal Surgeon Bowden died in 1814 and none of the more respectable surgeons in Sydney would accept the posting in Hobart, due to the poor reputation of the colony.

At the death of Bowden, Hopley was appointed Principal Surgeon but he too died just a year later, in August 1815.

In desperation, Davey appointed Assistant Surgeon George Bush, of the 46th Regiment, as principal surgeon. Convict Theophilus Mitchell was made acting assistant surgeon. Mitchell was a chemist and druggist, convicted of fraud and sentenced to 7 years transportation. Both Bush and Mitchell were paid from the Police Fund that had been set up by Macquarie years earlier.

In 1815 Macquarie appointed Henry St John Younge as assistant surgeon to the Hobart settlement. Younge had arrived in Sydney in 1813 having been appointed as a medical officer to the NSW colony by Earl Bathurst, Secretary of State for the Colonies. Shortly after Younge’s arrival Macquarie wrote a strong letter of complaint to Bathurst, that Younge was “ignorant as a medical man, being almost destitute of common understanding, and very low and vulgar in his manners.”

Macquarie complained that Younge was unsuitable to perform the duties of surgeon and that in future Bathurst would do well to make better investigations into the qualifications of medical officers before they are sent to the colonies. The only thing Macquarie could do now was to offload Younge to the Hobart colony as soon as possible.

Macquarie noticed on a financial report from 1815 that Davey had appointed Bush and Mitchell as medical officers in the Hobart General Hospital without the express permission nor even the knowledge of the Governor in Chief in Sydney. Macquarie was outraged. Not only had Davey made appointments without permission, he was paying a wage to a convict under sentence.

Macquarie demanded that Mitchell be sent to Sydney to complete his sentence and appointed Edward Luttrell (1756 – 1824) to the post of surgeon in Hobart. Luttrell’s family connections were to the English nobility and it was through these relations that he secured his position and land grants in Sydney.

Luttrell had a reputation almost as bad as that of Younge. On his arrival in Sydney in 1813, Macquarie said Luttrell was: “totally undeserving … deficient … in Humanity and in Attention to his Duty … sordid and Unfeeling and will not Afford any Medical Assistance to any Person who cannot pay him well for it”. Despite his incompetence, Luttrell was not suspended from his position in Sydney due to his large family of ten children.

Prior to being transferred to Hobart, Macquarie recommended to Earl Bathurst that Luttrell should be retired on half pay because he was “Criminally inattentive to his Patients … extremely Irritable and Violent in his Temper and Very Infirm from Dissipation”.

After Luttrell’s arrival in Hobart in January 1816, as the principal surgeon in the Hobart General Hospital, he proved true to form, neglecting his responsibilities and making false accusations. The convict hospital attendants were so poorly supervised that they freely helped themselves to the food reserved for the patients and dressings were changed only once a week.

Davey’s successor, Governor Sorell (1775 – 1848) repeatedly requested that Macquarie remove Luttrell. In 1818 Macquarie finally agreed and Luttrell was suspended from duties at the Hobart General Hospital, then retired on half pay. Sorell also succeeded in removing Younge from his position in 1818, on the grounds of neglect of duty, disobedience of orders, and disrespectful insubordinate conduct towards the governor.

It was another three years before the new principal surgeon, Dr James Scott (1790 – 1837), was appointed.

The functions of the Hobart General Hospital were on the verge of collapse due to staff shortages, and it only remained open because Sorell continued to call on military surgeons for assistance and paid them from the police fund.

At this time the hospital occupied rented rooms in private homes, then later whole houses. In 1818 John Cassity’s home was rented for £80 a year and the hospital consisted of two wards and a dispensary. Edward Spring was employed as wardsman and overseer, paid £25 a year. The hospital moved several times over the next two years and in 1820 it occupied Patrick Miller’s home in Liverpool Street. This had space for only 30 in-patients, and another 20 could be treated in the front room each day as out-patients.

The incurable patients were sent to a rented room at Fisk’s mill near Molle Street. The arrangements for the Hobart General Hospital continued to be completely inadequate for the population of over 5,000 people with hundreds of new arrivals each year.

After the end of the Napoleonic wars between England and France (1803 – 1815), the Colonial Office in London made funds available to resume public works in Hobart. It started in 1816, using convict labour. First was the new gaol, then extensions to the military barracks, followed by the military hospital in 1818. St David’s Church and government house, near Franklin Square, were completed in 1819.

Even though no permanent senior medical officer had yet been appointed, construction on the Hobart General Hospital began in December of 1819 based on the location and plans approved by Macquarie in 1811.

Governor Sorell preferred to locate the new hospital well away from the town’s fresh water supply of the Hobart Rivulet. He suggested a spot on the Domain, also known as the Government Paddock. Macquarie refused to use prime government land for what he saw as a convict hospital and declared the location for the new hospital would be in Liverpool Street, between Campbell and Argyle Streets.

In 1820, Commissioner John Bigge (1780 – 1843) (in VDL 21 Feb – 28 May 1820) was sent as Commissioner of an inquiry into the state of the colonies of NSW & VDL. When he arrived in Hobart, construction on the hospital was stopped to allow Bigge time to inspect the plans drawn up by the surveyor’s department.

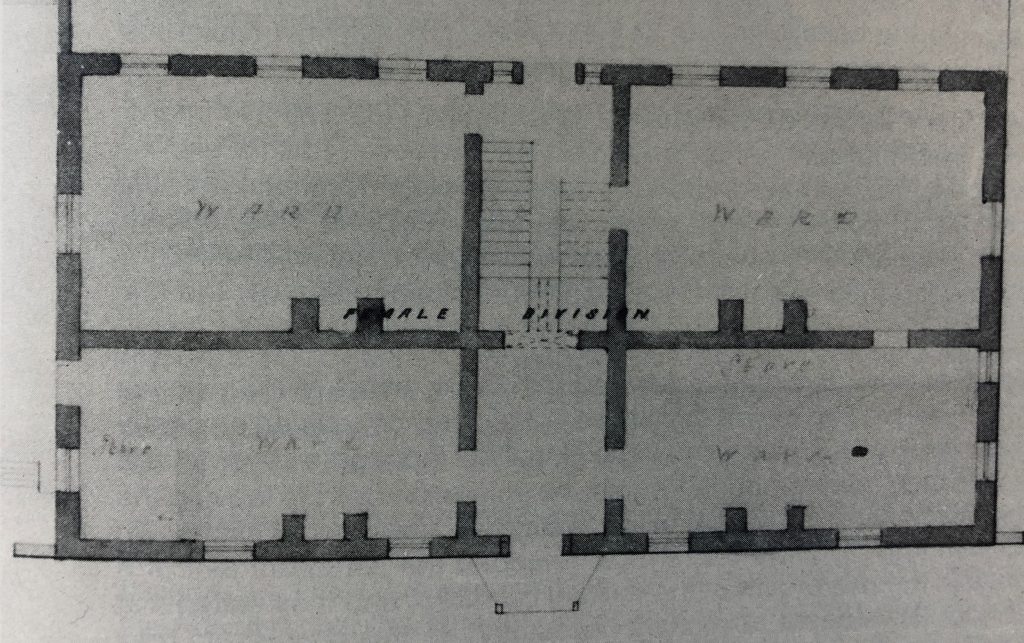

Bigge made some important modifications: he added separate hospital wards for male and female patients, improved the ventilation of the building and added toilets – none of which had been included on the original plans.

The two-storey sandstone building was completed late in 1820. It was in typical colonial Georgian architectural style, where the plan of the ground floor was matched by that of the upper level. In the main building, each floor consisted of two wards. Behind this building was a smaller annex of two wards, and behind that were two tiny cabins.

A 3-foot space was allowed between each bed, and each room had fireplaces. The plans allowed for the accommodation of 56 patients, with the possibility of another 28 if the beds were pushed closer together. However, far fewer beds were available as almost half the space was acquired for the pharmacy, records office, accommodation for the overseer and storage space for bedding and equipment. Other spaces were utilised for the kitchens and one of the small annexes became the lock-up for malingerers and the insane. As a result, less than half the planned ward space was available for patients.

A new, competent, principal surgeon was now urgently required. In 1820 Macquarie appointed Dr James Scott (1790 – 1837), who was a much better surgeon than his predecessors. He had qualified at the Royal College of Surgeons in Edinburgh in 1809 and served in the Royal Navy during the Napoleonic wars, after which he returned to Edinburgh for further training. Scott had arrived in Sydney in 1820 as the medical officer on the Castle Forbes convict transport ship and continued with the vessel to Hobart. From his first day in the post at the new hospital, Scott proved to be a competent medical practitioner and developed a good reputation.

The year after his arrival in Hobart he married Lucy Davey (1797 – ??), the daughter of the previous VDL Governor, Thomas Davey. Early in 1821 Davey sailed off to England and left his wife and daughter to fend for themselves. Governor Macquarie arrived in Hobart in June that year on another a tour of inspection. In the absence of Lucy’s father Macquarie gave the bride away at the ceremony in St David’s church.

Up until his death in Hobart in 1837, James Scott dominated the medical scene in Hobart and southern VDL. He attended to the medical care of civilians and convicts, seeing up to 50 in-patients and 40 out-patients daily. It was an extraordinarily busy role where each year a quarter of the population of southern VDL came to the Hobart General Hospital for medical treatment. Scott was helped by one assistant surgeon and 13 other staff members, all of whom were convicts under sentence: a wound dresser, clerks, watchmen, wardsmen and a domestic servant for Scott’s household. Dr Scott was also responsible for the supervision of everyone working at the hospital as well as other medical officers working in regional areas of southern VDL.

By the end of 1824 the colonial medical department working in the Hobart General Hospital in Liverpool Street was able to provide vastly improved medical care for the growing population of Hobart.

As surgeon, Dr Scott was considered to be delivering as good a standard of treatment as any other Australian colony. Hobartians were said to be content with the treatment and conditions of the Hobart General Hospital, confident that they were provided with sufficient medical facilities and expertise to meet their needs.

This has been an overview of the development of the Hobart General Hospital, with brief mentions of the key characters. There is some really juicy information about many of them and work is underway on the creation of some biographical information. It will be added here soon.