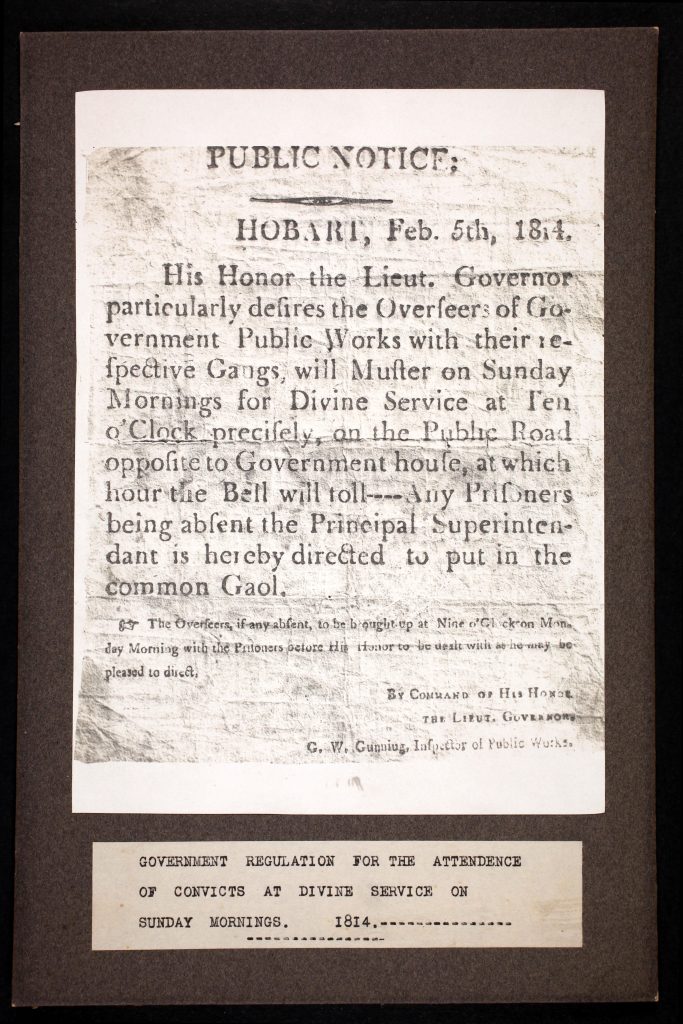

In the early days of Hobart, the only religious instructor permitted in the colony was the Church of England preacher, Robert Knopwood, who was in the employ of the governor. British settlement was seen as opportunity to instill in the convict population better moral habits and to convert the native inhabitants to Christianity. The Colonial Office believed the Church provided a necessary code for social order and control. Governors were required to ensure the observance of religion and good order in the colony through the practise of public religious worship.

There were never enough religious instructors available to attend to the spiritual needs of the whole island. When missionary preachers did arrive they didn’t display any great enthusiasm for the spiritual welfare of the convicts, and preferred a more comfortable assignment in more established regions.

Under Governor Arthur (1824 – 1836) religious instructors were employed to provide services for male convicts at the government work depots and convict barracks. Apart from pulpit preaching, the ministers avoided all contact with convicts. No attempts were made in moral instruction. When they did turn up to preach, it was at the timing of the preacher, at irregular hours and not on weekends. This caused great disruption to the work schedules.

Here is where the aim of the convict system was in conflict with its implementation, especially in the probation period of 1839 – 1854. Under Governors Franklin (1837 – 1843), Wilmot (1843 – 1846) and Denison (1847 – 1855), the object of the probation system was to reform and improve the convicts, and rescue them from evil habits. In practise the arrival of the parson signalled to the convicts it was time to down tools and take some time off.

Church of England was all powerful in the colony until the 1837 Van Diemen’s Land Church Act. This allowed for the ‘three grand divisions of Christianity’ – Churches of England, Scotland and Rome – to operate freely in the colony. By the early 1840s there was an increased presence of other denominations: Congregationalists, Wesleyan Methodists, Baptists, Quakers and Lutherans.

The Anglican High Church movement arrived in Hobart in 1842 with Bishop Nixon, trying to reassert its authority over religion in the colony. The first Roman Catholic bishop, Willson, arrived in 1844. Now the people of Hobart were spoiled for choice about where to spend their Sunday mornings.

Preachers of different denominations often shared chapels and were known to stand in the pulpit and preach against each other. There were also arguments over who should be the first to conduct a service on a Sunday.

The new 1848 regulations for convicts permitted them to attend services according to their preferred denomination – but none were allowed to choose not to worship. The command to attend church did not apply to the officers or free settlers. It is interesting to note that while all the convicts had to go to church each week there weren’t any reports that their morals had improved.

A new fashion in religious observance was driven by the Methodists in the 1840s. Participatory music was introduced in the form of congregational hymns and psalms. These were set to stirring tunes and became an attractive feature of worship, in particular in the many Methodist and Congregational Sunday Schools in Hobart. Many Sunday Schools had large libraries and were centres of literacy and numeracy for the children of the working class. The popularity of Sunday Schools waned with the introduction of free state school education in 1908.

The 1861, 1891 and 2016 Tasmanian censuses show the spread of the denominations as stated by the population:

| 1861 | 1891 | 2016 | |

| Church of England | 52% | 51% | 21% |

| Catholic | 22% | 18% | 15% |

| Presbyterian | 10% | 7% | 2% |

| Methodist | 7% | 12% | |

| Congregational | 4% | 3% | |

| Baptist | 2% | 2% | |

| No religion | 38% |

Keep in mind that there is a difference between stating a denominational preference and regular church attendance. By 1855 convict transportation to VDL was at and end. As convicts continued to work off their sentences, they were still bound by the same rules of church attendance. The convict system ended in 1877 and finally all Tasmanians were free to attend church services or not.