Image: TAHO

As you head into this long weekend for Hobart’s Regatta Day (thank you Governor Sir John and Lady Jane Franklin for starting that bit of fun in 1838) you are probably thinking about the next long weekend next month, on Monday 9th March 2020: Eight Hours Day.

While the February long weekend is given over to all things nautical, the March event has its origins stretching back to even earlier, with the start of worker organisation, including strikes and unions.

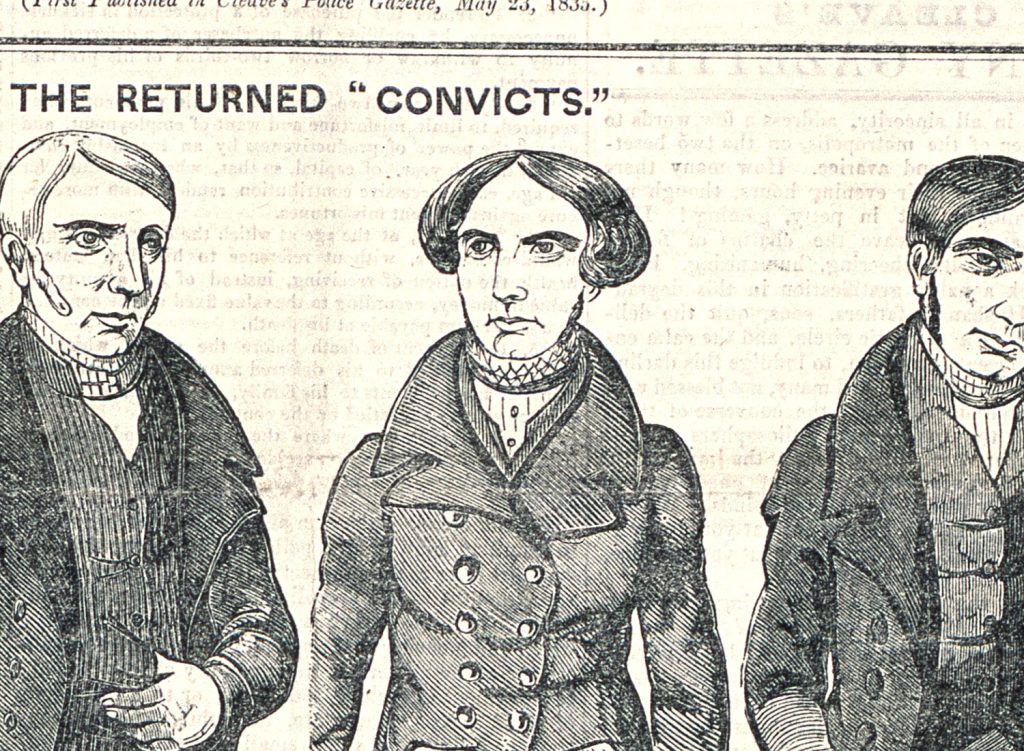

Transported convicts to VDL knew about, and had experience of, centuries of formal and informal collective action against exploitative employers. Many of the industrial and political activists like machine breakers and a couple of the Tolpuddle Martyrs (1834) were transported to Hobart.

Image: Cleave’s Penny Gazette

Groups of convicts and free workers went on strike over wage disputes, workload, working conditions and hours. Between 1804 and 1849 there were over 100 occasions in VDL where workers banded together to seek an improvement in conditions, and half of these involved collective strike action. These actions doubled over the following 30 years to the mid-1870s when more formal collectives were established.

In the early years, the industrial action was predominated by whalemen and seafarers; then from the 1820s skilled tradesmen like builders, tailors, bakers and bootmakers organised unions to bargain for better wages and conditions with employers.

Initially the union groups met in pubs, but by the 1860s it was decided that meetings should be held in Temperance Halls as after an hour’s meeting in a pub no one was capable of making a sensible decision.

In 1842, general and postal clerks in Hobart went on strike for higher wages, and 1847 retail workers followed suit to secure shorter working hours, followed by a cab driver strike in Hobart in 1848. The cab drivers objected to the introduction of a cab drivers license and extensive driver regulation – as well as the 10-shilling fee that came with each license. The result was that suddenly there were no cab drivers left in Hobart to be regulated.

The Hobart Trades Union formed in 1847, as did the Mercantile Assistant’s Association and industrial action became more organised and focused.

Unlike the colonies in Victoria and NSW, Hobart’s union movement was slower to become firmly established, due to VDL’s slower economic growth and the loss of labourers to the goldfields on the mainland. During the 1850s the push for an eight-hour working day began, which was met with stiff resistance by employers.

While the administration of convict labour and working conditions was detailed and intrusive the regulation of free labour was not. Convicts under the assignment and probation systems knew what they were entitled to and were quick to complain if they felt their food or clothing entitlements were not provided by an employer.

Emigrant workers however were not so lucky, especially domestic workers who frequently had to bring a charge against unreasonable employers. Prosecutions were an everyday occurrence in the lives of workers in VDL and NSW: hundreds of thousands of cases of disputed working relationships in NSW & VDL were brought before 1850 – for a combined colonial population only 405,000 Europeans.

Employers and employees were not equal before the law: in 1836 Magistrate Windeyer ruled in favour of Mrs McGuire who had employed a female migrant to work as a laundress. Mrs McGuire insisted that the girl work on Sunday and not have the day off to go to church – an instruction which was refused. Magistrate Windeyer told the unfortunate washerwoman that menial servants can’t claim the right to go to church on Sunday, but were bound to give service to their employers on Sunday as any other day.

Industrial relations were a one-sided regime where courts routinely imposed severe penalties for minor infractions and dissent. Unlike in England, domestic workers in VDL were on demand at all hours. Female convicts under sentence developed their resistance tactics mostly through what was termed as “misconduct”: they would refuse to take orders from anyone else in the household except that particular person to whom they were specifically assigned. The Master of the house was generally the one to whom the female convict domestic servant was assigned – but her work was under the instruction of the Mistress who had charge of the household work in the laundry, kitchen and cleaning the house.

After the end of transportation, and the name change to Tasmania, it was imagined that conditions would improve for employees. They didn’t.

In 1877, bootmaker Batt brought charges against his apprentice Cantrill who refused to work more than 11 hours a day. Unfortunately for Cantrill he was prosecuted, fined and charged costs under the notorious 1854 Master and Servants Act which governed the relationship between employers and employees. It gave sweeping powers to employers and employees were punished for breaches of the act.

Some of the more choice conditions of the legislation included the legal right of the husband to tell his wife to quit her job if she took a position without his consent. Wages were payable quarterly and employers were known to time their charges against their employees for some minor offence just before pay day. A successful case against the worker meant that all unpaid wages would be forfeited.

The legislation details that workers were legally obliged to perform their duties in a diligent, respectful and careful manner, with no misconduct, insolence or other poor behaviour – subject to 3 months imprisonment with hard labour.

Other prosecutable behaviours include using any abusive, profane, or obscene language to or in the presence of the master or any of the family members; being absent without leave for any period of time; being unruly or insubordinate, drunk or disorderly whether at the home of the Master or elsewhere; if a female – behaving in an immoral fashion. In all cases, all costs were to be paid by the losing party.

If a successful case were brought by the worker against a master for the non-payment of wages, it was up to the magistrate to decide if there was a case to be brought against the master. If found liable, the master would pay a fine of up to £20, at the magistrate’s discretion.

Employers of migrant workers were entitled to withhold half the wages of the workers until the total cost of the passage money and work clothing was recouped by the master.

No one else was allowed to hire the servant or apprentice of another master before the initial term of employment had been completed.

You can see now why it took so long for the union movement to be able to organise itself sufficiently well before it had the strength to pressure employers into better pay and conditions for the workers.

Things moved more rapidly in the other colonies: In Sydney, October 1st 1855 saw the introduction of the eight hour day for the Stonemason’s Society, the members of which went on strike during the construction of the Holy Trinity Church and the Mariner Church. Stonemasons in Melbourne followed suit in 1856 and from 1879 the eight hour day was a public holiday throughout Victoria.

In the 1870s there was still strong opposition to the eight hour day in Tasmania, with business owners and employers insisting that anyone who only worked eight hours a day would be reduced to pauperism and would prevent the country becoming prosperous. They assured the workers that it was better to work 16 hours a day while they were still young in order to save up for their old age. The landed gentry declared that a population that only works eight hours a day will just waste their time in foolish pursuits.

Undeterred, by 1874 the bakers of Hobart had succeeded in reducing their hours to 10 per day, at no inconvenience to the public, nor a reduction in quality of bread or its delivery. The City of Hobart Corporation refused to even consider an eight-hour day for their workers, but agreed to half-day on Saturday for labourers. The concession made by the banks in Hobart was to close at 12 on Saturdays instead of 1pm.

From the 1880s there was a significant growth in the range of trade unions in mining, engineering, railways and building trades, especially after the Tasmanian Trades Union Act was passed in 1889, which legalised trades unions and the general principle of an eight hour work day was widely adopted.

After that on March 6th each year, a procession through the streets of Hobart was organised to commemorate the establishment of the eight hours day in Hobart. It was so well attended by the city workers that the government offices and banks were closed, causing it to become a general public holiday. Few people lined the streets because most of them were in the procession, with decorated wagons and brass bands.

In 1891 the first nurses association was formed in Launceston, along the same lines of the British Nurses Association, so that its members could be assisted and registered as qualified nurses.

Due to the economic depression of the 1890s, it was typical for most trades unions in Tasmania to fold within five years and hostile employers refused to hire any union members. In particular the Hobart Trades and Labour Council collapsed in 1897. In other states, the Labor Party was established from the trade unions, but not in Tasmania. The Tasmania Labor Party formed in 1903 under the presidency of John Earle (1865 – 1932) later Premier of Tasmania for one week in 1909, then again for two years 1914 – 1916.

Image: Wikipedia

After Federation in 1901 things improved for workers in Tasmania with the establishment of government industrial tribunals, known as wages boards in 1909. This, along with the formation of the Tasmanian Labor Party, led to a renewed interest in the support of unions, especially as their key industrial object was to secure an eight-hour day for all workers. Branches of mainland unions were established in Hobart, and conducted successful strikes on behalf of member, in spite of strong opposition from employers and the press.

After the First World War the Eight Hour Day was celebrated with street parades in Hobart, in particular during the 1920s.

So if you are wondering who to thank for the gift of yet another public holiday in Hobart, go shake the hand of a union organiser.